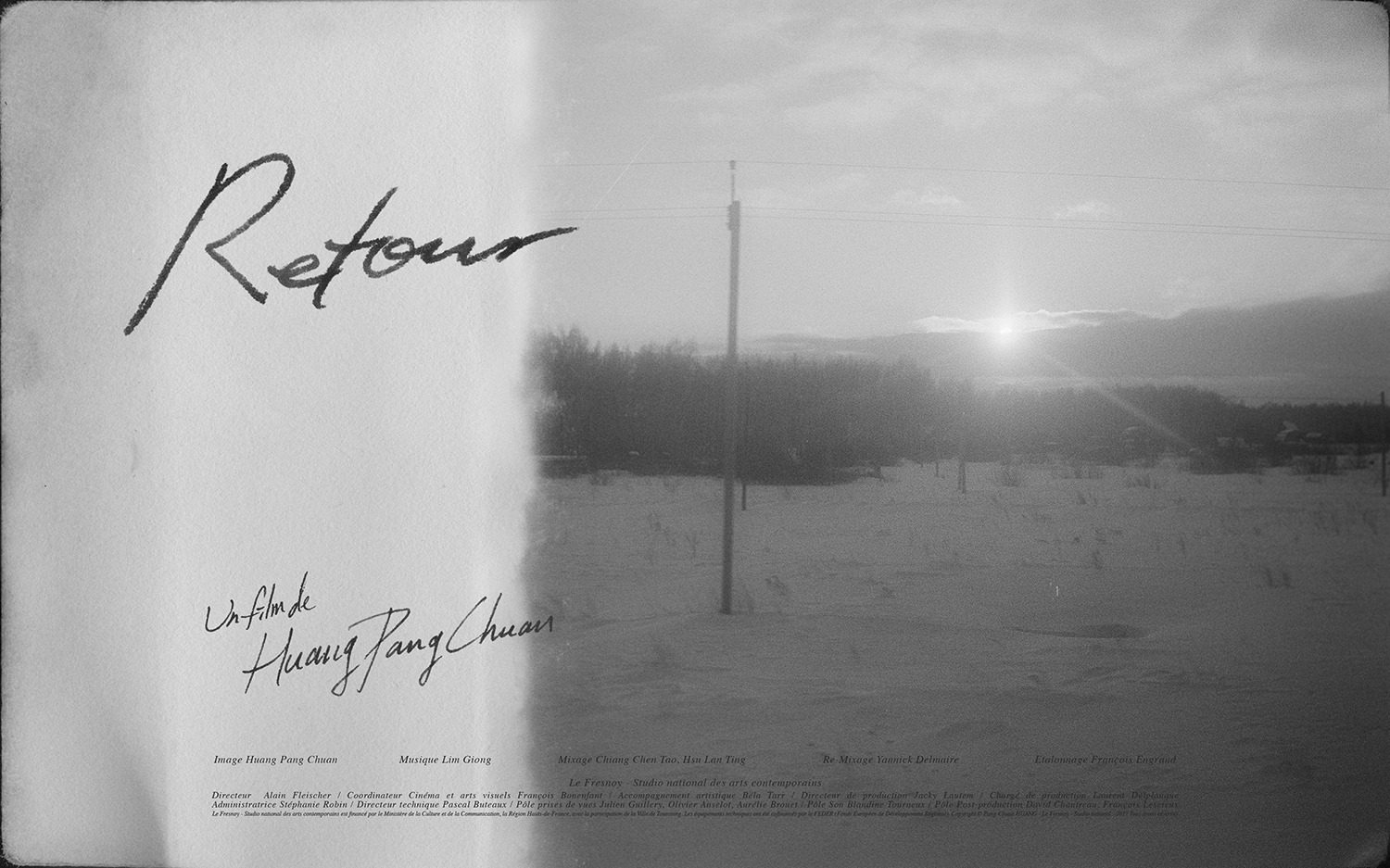

HUANG Pang-chuan, born in 1988, had been working as a graphic designer, photographer, and film editor for several years, before he enrolled in the course “Cinema and Audiovisual studies” at Sorbonne Nouvelle – Université Paris 3 (France). After graduation, he was accepted as artiste étudiant into Le Fresnoy - Studio des arts contemporains. Return is HUANG’s first film, which he completed after his first year of studies at Fresnoy . It had been screened at several festivals in France and Taiwan, and gained the 2018 Clermont-Ferrand - Lab competition Grand Prix Award and the Special Jury Mention of the TIDF 2018 Taiwan Competition.

Photographic Negatives

Return is about a journey in search of memories, told in two parts. Poetic and creative in form, the film deals with HUANG’s own past and that of his family. The film is mostly construed from stills, shot on a Canon EE Demi 17 manual camera. Huang explains: “This is a half frame camera, as it was popular after World War II when materials were scarce. With a half frame camera, you could fit twice as many pictures onto a standard roll of film. It was often used for practice, or for children to play around, almost like a toy. Because I was taking one photo after the other, all three cameras I used broke, so in the end, I had to use a normal camera to finish my work.”

On this long trip through Europe and Asia, HUANG’s luggage had to undergo numerous inspections, which left some of the negatives damaged by X-rays. HUANG says: “Probably nobody would notice, but those damaged pictures appear in the section of the film where the massacre is mentioned. I think that fits quite well.” He is fascinated by photographic negatives for their uniqueness, their irreversibility, and the special feeling that they evoke.

Memories

If a film is assembled from stills, Chris MARKER’S La jetée (1962) inevitably comes to one’s mind. HUANG admits to being influenced by this work. “For me, La jetée is like a piece of ethnological research, but I wanted to do something warmer.”

Can we find this warmth in HUANG’s film? It comes with a sensitive, detailed voice-over, a quality of light that only be achieved with an old, manual camera, and HUANG’s handwritten titles for the different chapters of his film. And, of course, there are the memories of his family, and reminiscences of an epoch gone-by that build the background of his work. When asked for the motive to make this film, HUANG answers: “I have always had an interest in letters and diaries. Before I left for France, I learnt that our old family house was to be renovated. When I went to the old home, I found a suitcase with old pictures, letters and diaries; in other words, a suitcase full of memories.”

On top of having all those written documents and pictures, he also put a lot of additional effort into collecting oral materials from his family members. Still, those memories would remain odd and fragmentary. HUANG would go over them again and again, weighing every word, and putting the pieces together. In his opinion, historical documents have to be respected, but at the same time, he wants to give room to his own imagination of the past. Due to the distance in time, reality becomes blurred and therefore impossible to be accurately described. In HUANG’s view, one has to embrace the present moment to look at a story from the past, and use one’s creativity to give new life and meaning to it.

Not only personal memories, but also the meaning of history can be revived through creativity. Although Return is based on a family’s history, concrete historical references and place names were eliminated in the voice over. Thus, the film is not so much a tale about a person’s life in wartime China and Taiwan, it is more like a mirror reflecting the human condition in general. Difficulties of language barriers, the impact of war, the displacement of people being forced into homelessness and migration, all those problems that are not limited to the boundaries of individual countries, are alluded to in his film. When screened at the 2017 Poitiers Film Festival, HUANG’s film was praised in the discussions to decide the Human Rights Award because of its humanistic sentiment, as HUANG gratefully remembers.

Travelling

HUANG prefers situations that cannot be controlled, for example encountering the uncertainties of travelling. “What influenced me most in TARKOVSKY’s films is this elementary force that cannot be controlled.” Unforeseeable first-times never fail to have an impact on HUANG. The realization of his plan to venture out for this long trip, might have finally been even more important than the narrative in the film. When we are creating something, our imagination can achieve a lot of things. If we entirely rely on the narration, we would waste our ability to imagine.

In the early stages of the creative process, there were only the family memories and the idea that a railway journey would be the starting point. He didn’t really anticipate what was to be seen or heard during the trip, he only meticulously documented all the images, sounds and impressions he encountered. Once he returned, he started the editing work, selecting from an enormous pile of material. “I want to tell my story with simple means. For instance, I am always using old-style photography. As for working with negatives, the easiest way is to either enlarge them or to show parts of them.”

Another impressive narrative element in his film is the use of sound. HUANG uses realistic sounds that he recorded during the journey, from inspiring surrounding sound sources to interesting dialogues from passers-by. The soundscape’s repeatedly occurring details create a vast imaginative space. “If it comes to editing, I think that rhythm and sound are even more important than images. Actually, the sound tracks were often randomly piled together. I would just close my eyes and listen, until it sounded pleasant to me. I wouldn’t be able to repeat this process. The only exception is at the end of the film, when the sounds from my repertoire seemed inappropriate. So, I asked LIM Giong, the sound designer of my film, to add an extra sound. “I was abroad when I was looking for a sound designer for my film. I contacted LIM Giong by email, at a time when my film only existed as a proposal.” LIM Giong added his music at the very end, when the editing with all the images and sound effects was finished. After that, there were no more changes.

When his film was screened at festivals in France, HUANG observed how the audience reacted to the soundscape: “As soon as the typical sounds of the French railway stations could be heard, the whole theatre was laughing. It was so familiar to everybody. Because he pays so much attention to sound, he decided to read the French voice-over himself. “I speak French with an accent. The Taiwanese audience wouldn’t probably pick it up, but the French would immediately know that a foreigner is speaking. Likewise, when a dialogue in Chinese occurs, it sounds very familiar to a Chinese speaking audience. This reminds us that language can create a warm, nostalgic feeling, but it can also lead to ethnic division. HUANG uses language for both purposes: To make us realize what it means to be a stranger, and to convey the feeling of belonging to one’s own country.

Asked about directors that he likes, HUANG mentions HOU Hsiao-hsien. “I particularly like the last scenes of his films, and his way of using music. He never wraps up a story at the end, but lets you take the film back home so that it continues to resonate within you”. The last scene of Return has this kind of magic. It is the only part of the film where HUANG used a Super 8 camera instead of a still camera. It is a touching scene, which does not seem to be the end of the film, however. Rather it seems to be a gentle question, asking us where we come from, and where we are going.

Translated by: Stefanie Eschenlohr