I. History and Reality

On certain extent, documentary as an “end result” has often times tolerate difficulties and happiness that were falling behind “era (time)”, “people” and even “reality” through looking from a distance.

“Falling behind” implies we can still trace a kind of reality closer to “truth”, which we could never perceive. Among the causes would probably be the dislocation of time, distance between concepts, complexities of realities under different conditions, or even misty and unknown aspects as well as memories in the stream of history when confronting diverse minds and considerations.

Hence, to make a biography based on a poetry society gathered 80 years ago, we felt there is no solid ground. If we want to achieve an “oral testimony”, there are fears if pain of the interviewees’ would be provoked when confronting vague memories or things they couldn’t tell. If we try to stand by the side of those who had passed away, as if propagating in their voice, it would bring even more anxieties and worries. Both for the filmmaker and the subject, the ground to apply forces is so fragile and negligible when we are facing history. How could we voice out the negligibility? Moreover, when gleaning pieces of others’ life, we could only put historical “truth” that we understand into order after going through all the accumulation process.

On this foundation, Le Moulin (2015), a documentary based on the Moulin, a Taiwanese poetry society, confronts a situation, both in the beginning and in the end that the parties concerned are absent, and they then become the viewing and narrative subject of later generations. Without “testimony” of parties concerned, their successive family members became their “legal” spokesmen. Through interference of the filmmaker, remained memories of their successive family members went through selection and imagination process again and again, being stirred repeatedly through shootings and interviews.

This indeed is extremely difficult.

During this lengthy process, the ethics of documentary were far more complicated and delicate than we could imagine. The ethics not only often reminds but also interferes the view and interpretation of the filmmaker. It also questions the filmmaker if they have already thought through. Who has the right to interpret? Who should accept these interpretations? What do these interpretations tell? The complex relation between the filmmaker and the subject went back and forth vigorously between history in the past and current moment. These have become our attitude when confronting “history”. “History” is no longer an empty or abstract term, but something concrete and delicate. Every detail relates to us personally, and “history” is as the ocean of memories. An ocean without borders and waiting to be filled, letting the later generation to be confused.

However, why did the filmmaker still naively and eagerly pursue the possibility of “historical truth”, even if knowing the impossibility to “reenact” history? For me, the foundation of making Le Moulin probably came from concerns on “the past used to exist” and believing that “historical truth” could be approached and inquired. However, seeking historical truth is not a mere parallel to study or photorealistic pursue in fiction films. It relies more on the interaction between the filmmaker and the subject or the theme. The filmmaker put himself in the position of the others and feels what the others feel. He then would further respond as well as reflect, throwing his own self into broken pages of history. The filmmaker would feel confused, sad, doubt, questioned, ignorant and stuck, facing more and more uncertainties. All these will then gather, transform into conversation and self murmur that go beyond time and space, reverberating within different characters and incidents. These struggles reflect uncertainties or even the unknowable in the vast stream of history. They form various complexities in peoples’ cognition, understanding and conviction at current times.

Standing on these grounds, documentary shouted silently.

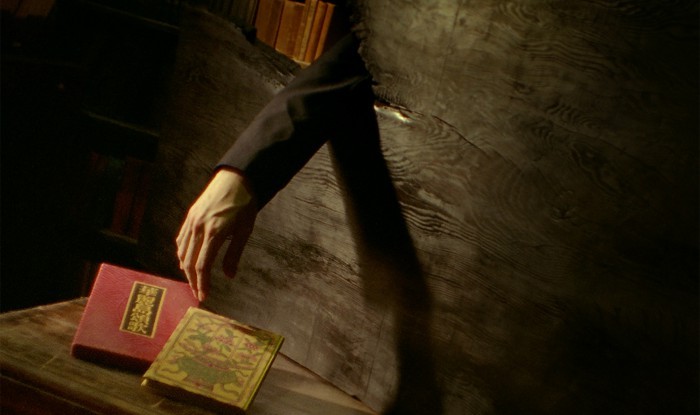

After broken pages of history being conceptualized by the dailies, and continue to show themselves in various facets, be it mottled black and white old photographs, trembling and rough eight-millimeter film, murmurs of memories of the elderlies, yellowish old newspaper and manuscript, different languages and words interpreted by different ideologies in different era, clues in the opposite…But, truth of history seems to be drifting away (or was already in non-existence since early on).

Hence we will come to know gradually, that we could never shape the absolute past in history when we are in the current times. At most, one could only think and discover more through this exploration process that was given deep thoughts. From it we could probably get closer to historical truth in a deeper way, including how to think of a poetry society that cross the boundaries of culture, context, identity and many others, as well as to think of the complex meaning behind. How to store and sort out people and matters that were either directly or indirectly linked in broken pages of history? How to continue question and examine objectivity and rationality from clues in diverse sides? How to look for possibility of conversation in the absence of parties concerned? It seems to be a process where the filmmaker was facing history from only one side, and raised question individually. But this process might allowed the filmmaker to be lucky enough in pursuing precious moments of the short return to historical “truth”.

II. Two Sides of “Colonization”

How could a filmmaker who had never lived through the times of colonization interpret a literary experience of the past? This question pointed out not only the living “reality” of parties concerned, but also Taiwan’s internal and external changes of politics and economics in the post-war years, as well as imagination and interpretation (and even more reinterpretation) on Japanese colonization after the political power shift, particularly the long term collective suppress and silence after the war. The fact that people could not talk and dare not discuss about times of Japanese occupation has formed an empty space filled with aphasia and fractures in Taiwan historical narrative. In 2015 Taiwan, what is the historical interpretation intertwined by these complex causes? And as a successor of traumatic experience, how could we carefully touch these wounds?

Le Moulin during early 1930s, had experience the degenerative of their ancestors’ anti-Japanese movement. These Taiwanese poets create literary works in Japanese language. They were active during the early Japanese Showa period. Gathering together the Japanese poets growing up in Taiwan, they attempted to bring in a new literary force to the literary scene. When were strongly aware of the difficulties to fight against colonization through literature, they then turned into searches and longing for newest literary forms diverted from Japan. We could of course notice the direct passion of these poets towards literature. However, their questions on colonization were also hidden behind those passionate pursue. (We have to be aware that this is a poetry society co-constructed by Taiwanese and Japanese. After all, were there only Taiwanese members that have the intention to fight against Japanese regime, or it actually included the Japanese members? These issues remain a forever-unknown empty due to the lack of information of their Japanese members.)

And today, to criticize this poetry society by using anti-colonization theoretical structure is indeed the most direct and convenient gesture of resistance. It has also become the most rational foundation for most critics. However, the more the theoretical structure was implied, the easier it could reveal dogmatic and monotonous language. There is danger to loss conscious on subjectivity if avoiding this issue. But maybe we can reflect again that how could we allow more spaces to include uncertainties between “colonization” and “anti-colonization” when debating on the two questions? How could we recruit those who were included in the minorities, individual or those of different race, as well as righteous living gesture that was always being classified as “the others” under the mainstream discourse. In a peaceful era of assimilation, how could “anti” colonization tactics of literary people reveal the question and turn over reality? And when writers put all their effort in mere literary writing and chose to avoid the “anti” colonization reality, how could people in contemporary society understand and deal with this matter? How many living struggles and realities on colonization history intermingled between “anti” or “not to”?

Such literary experience of modern literature like Le Moulin has forced us to confront, that even during the end of 1970s, when Shuiyin Ping, the founder of Le Moulin was still alive. We inevitably include words left by him or by this pre-war literary generation in “brackets”, due to the heightened political condition after the war. And this “bracket” not only brings in distance between the successor and historical truth, but also almost declares the helplessness, that truth can never has a solution, and can never be re-enacted. The forever “suspension” pointed out the most realistic and harsh situation confronted by the “cross-language generation” during Japanese occupation.

III. Literature and Politics

Stepping back on “art for art’s sake”, a popularly simplified concept in contemporary society was already transformed into different facets as early as mid 19th century, following the thinking trend within intellectuals in France, Germany and England. Influenced by autonomy and creative concepts of Western literary scene, the Japanese literary scene in 1920 triggered various oppositions between the “live group” and “art group”. This even directly or indirectly affected Chinese students who were studying in Japan at that time, and eventually initiated similar arguments in China. During the late Taisho period, poetry scene in Japan has divided into three stands, the “art stand” that insisting on intellectualism and innovation, the “societal stand” holding onto position of the proletariat, and “the third stand” proposing destruction of traditional order. All these, could not be simply divided into “imitation” and “appropriation” of the West.

In other words, if it is not to make a decisive conclusion that “art for art’s sake” was an imitation of the West, and that the discursive module triggered by “art for art’s sake” was not an appropriation of the West, then probably the more important question would be, why was there a strong need for these imitations and appropriations among people in the literary scene at that time? How many causes and conditions were hidden in order to make those requirements tenable? What are the hidden questions accumulated within?

Maybe we should try to experience and observe from literary point of view, that why people in the literary scene were keen in developing a quest into the internal, as well as looking into uncertainties of human nature and psychology in a more delicate manner during the end of Taisho period and early days of the Showa period? We then notice matters that attracted poets in Le Moulin, which include YOKOMITSU Riichi’s materiality new sensations, KAWABATA Yasunari and TANIZAKI Jun'ichir?’s decadent and obscene, NAGAI Kaf?’s indulgence in beauty and freshness, AKUTAGAWA Ry?nosuke’s art above everything, JEAN Cocteau’s flying imaginations, Paul VALERY’s intellectuality and order. These are the most important part of literary thinking from second half of 19th century to early 20th century. Since the beginning of 20th century, Japan had been absorbing literary progress of the West in its’ highest speed. Under the education system of their colonial mother country, Le Moulin’s poets were swallowing and receiving huge literary waves coming from all over the world. They then strained their own modest energy, calling the participation of Taiwan literary scene.

Probably as described by Japanese historian KATO Shuichi, Japanese youngsters from 1918 to 1923 was a generation of the “1900s”. He also argued that they experienced the West through imported books. And the Europe and America that they envisioned were already being translated, rather than first hand experience. Not only Japanese literary scholars had more ambitious imagination towards imperialism and nation state, Le Moulin’s poets born in Japanese colony were also successor of this generation. They even strengthened layers of gearing and slowly formed sense of identity through convenient and new experience on modernization. Simultaneously, inevitably various kinds of contradictory emotions will occur when they encounter divergence in social status due to their identity as the colonized. If seen from the history of the colonized, of course it will be “politically incorrect”.

Although Le Moulin on one hand hold onto mixed avant-garde spirit of surrealism, New Sensation School and other forms, and on the other hand maintained friendship with Japanese writers through writings. This doesn’t imply that Le Moulin had no understanding on Marxism or leftist thinking, or naively followed the West and the Japanese. However, was there any space that could accommodate them in that era? Or the history had brought them to a corner at the border and they could only warmed each other?

It is a miracle in literary history that short-lived literary group such as Le Moulin had a chance to be found accidentally during the 1980s. This is not a surprise chapter in the post-war Taiwan historical context, for it revealed probably there were more being buried under ashes of history, and never to be seen again in literary history.

IV. Crossing

Looking back at traces of these Le Moulin’s poets, they retrograded by putting in all their efforts but no echoes were left behind. These traces were full with intermingled unspeakable and complicated living conditions. No matter how these Le Moulin’s poets beautified things, they need to confront the reality, that the time would not wait for them. Although it brought sadness and beauty but inevitably, they need to face their final destiny. “You can avoid politics, but politics will come for you”.

Though Le Moulin’s poets were finally being regarded as a “cross-languages generation”, they didn’t cross over languages and could not cross over politics after all. Hence when people tried to make their final evaluation on Le Moulin, be it defining “art for art’s sake” as an escape from politics, or seeing their ideologies as a kind of political resistance. Both explained the openness and multiple layers of literary arts.

Le Moulin might be short-lived, but it’s aspiration towards the freedom and innovation of literature, as well as their insistence on not to be bound by any structured forms, both might be seen today as overly pure. However, it is because of this purity that allows us to feel and get closer to that era, be it eighty years ago or eighty years later today.

For more information about Le Moulin: http://docs.tfi.org.tw/content/59

(Translated by AU Sow-yee)